3 React Component Patterns Every React Developer Should Know

Master the patterns and build whatever you like with confidence

When I started learning React, I didn’t care a lot about the patterns that made my code reusable. I just used to write all the functionalities and all the state management logic in its own component. But soon I began to realize that wasn’t the right way — my code was very unprofessional. I started to research the component patterns to make my code reusable and scale properly. So here are three React component patterns that I now use in every project — you probably should too.

Note: I’m going to showcase these patterns in React Native but obviously these patterns can be applied to any React projects.

1. Compound Component Pattern

Compound component pattern is by far my favorite React component pattern. You might be familiar with <select>…</select> element with <option>…</option> elements as children in the HTML world. This component pattern follows the same principle:

<label for="dunder-mifflin">Salesman of the year</label>

<select name=”salesman” id=”dunder-mifflin”>

<option value=”dwight”>Dwight Schrute</option>

<option value=”jim”>Jim Halpert</option>

<option value=”andy”>Andy Bernard</option>

</select>

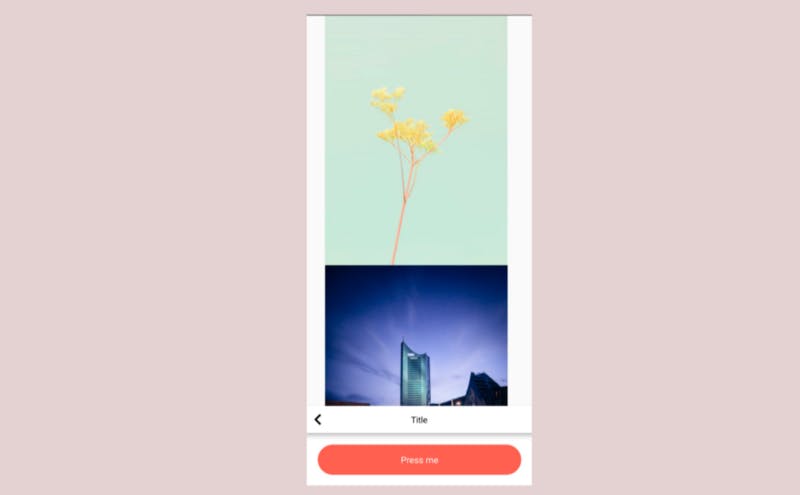

I commonly use this pattern to separate my header content, body content and footer content in my every React Native project (I like to call this component Layout). We know that every mobile apps has a header component for navigation and showing title, and the main content that can be scrolled in the middle and has a footer that may contain buttons at the bottom (footer may not be common though). Let’s demonstrate this with an example app:

Base Layout with header and footer.

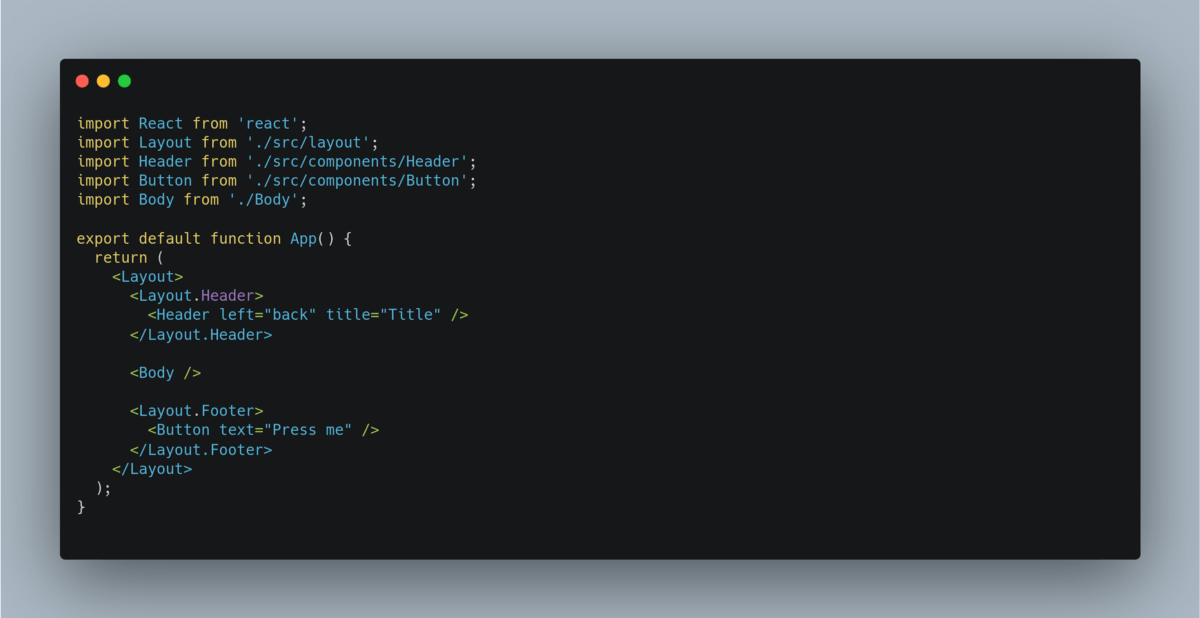

The code for the above render simply looks like this:

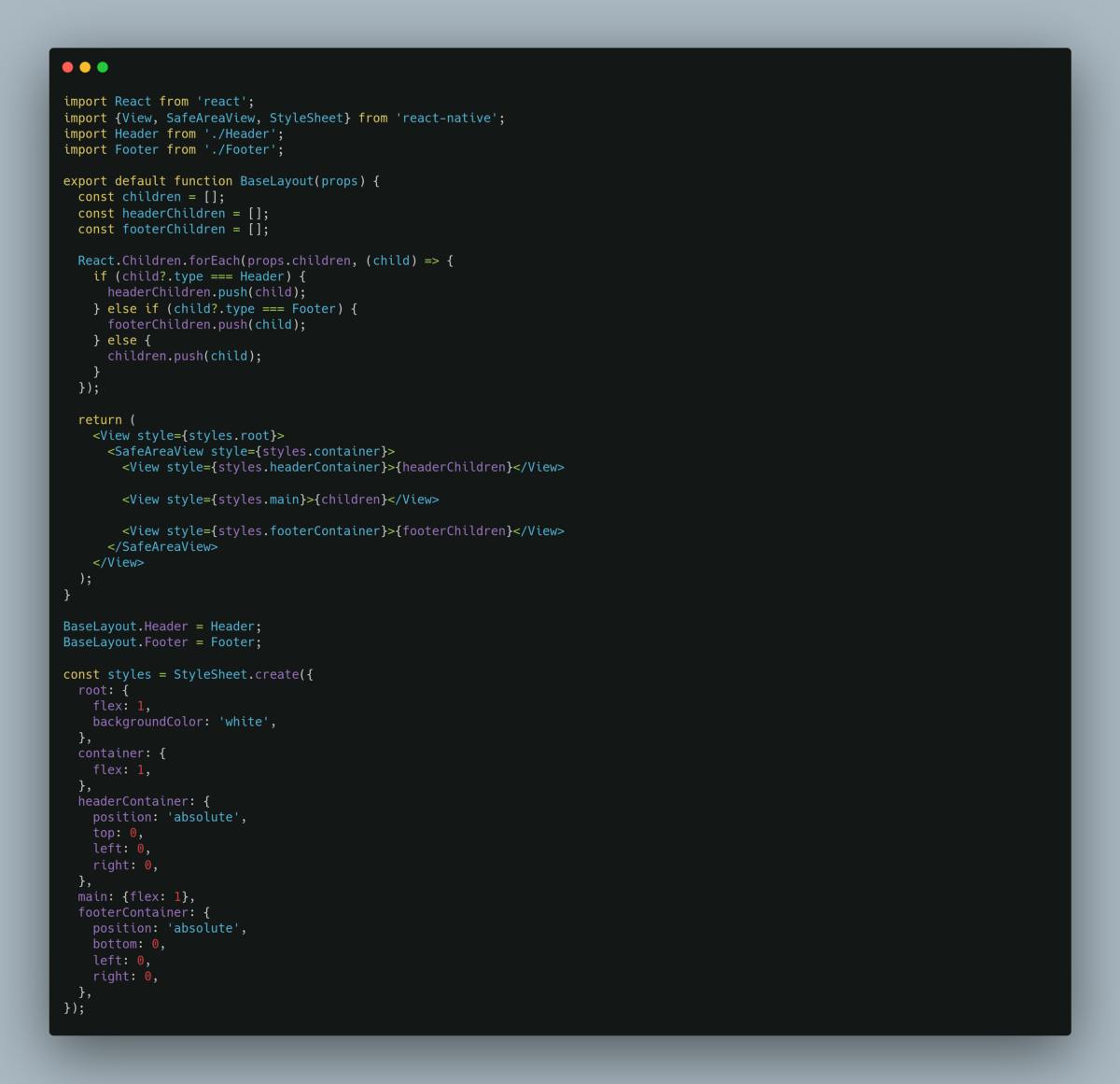

Simple right?. This is a typical Layout container with header inside <Layout.Header>…</Layout.Header>, footer is inside <Layout.Footer>…</Layout.Footer> and any other things that not inside Header and Footer will automatically be rendered as body. But how does this work? That’s where the magic happens, so let’s break it down. The code for Layout that utilizes the Compound component pattern looks like this:

So, Header and Footer are two components that we import in the Layout component and register them to Layout component with the same name.

We check the types of child passed to Layout before rendering so that **<Layout.Header>…</Layout.Header>** and **<Layout.Footer>…</Layout.Footer>** will be of type Header and Footer child respectively and any children inside those will go to their respective components. Any other child besides Header and Footer will go to the body section of the Layout component.

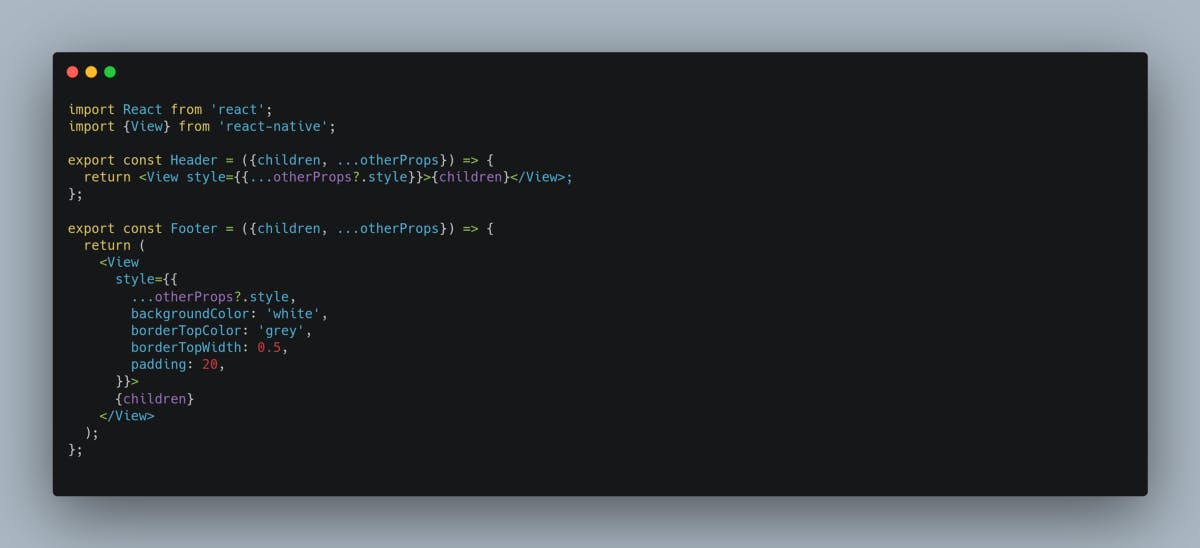

Now, apply some styles to the respective containers and you’re good to go. Here’s the Header and Footer component (*Header* and *Footer* components are shown in the same file here).

But there’s one crucial thing to consider in the Compound component. What happens when I apply <Layout.Header>…</Layout.Header> and <Layout.Footer>…</Layout.Footer> without wrapping them inside <Layout>…</Layout> parent? Like this:

You will find that the layout remains the same here (wait…). That is because the layout now although is not part of the Layout component but due to their sequential order they look exactly the same. So go ahead and move the Body component to the top and see the changes, the layout will be messed up. (Previously Body component can be anywhere when wrapped inside Layout)

Without wrapping inside parent Layout.

We don’t want this to happen, ever. To preserve our layout we should always wrap them inside Layout parent. So, we need a way to show an error or just display nothing when they are not wrapped. We can solve this problem by leveraging React’s context API.

We simply have to wrap whole content inside a provider that simply supplies any value ({valid:true} here). The idea is if we get that store value in the consumer then we display them otherwise display null. Since Header and Footer are the children of the Layout component so if they are wrapped inside Layout they will receive the context value, otherwise they wouldn’t. So we just check for that context value and display conditionally.

Now the layout won't be messed up when Header and Footer are not wrapped inside the Layout parent. Instead only the Body component will be visible.

Other use cases of the Compound component can be implementing tabs:

<Tabs>

<Tab name=”Incoming” />

<Tab name=”Outgoing” />

<Tab name=”All” />

</Tabs>

2. Render Props Component Pattern

Render props component pattern is another great way to leverage the code reusability. I use render props pattern to do tasks like toggling a modal or share button, or to manage the state of Activity Indicator, to name a few in React Native.

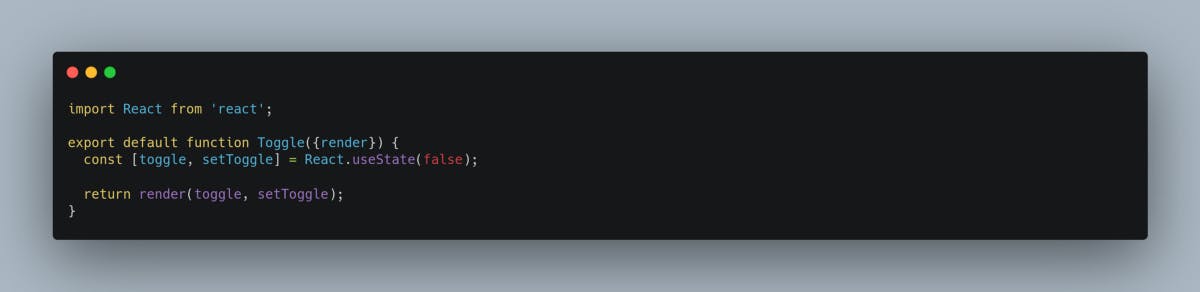

It simply means passing props named “render”(hence the name) that is a function to a component and invoking that function in the component so that the resources can be passed back. It can be a little confusing for the first time so let's see an example using a simple Toggle RPC.

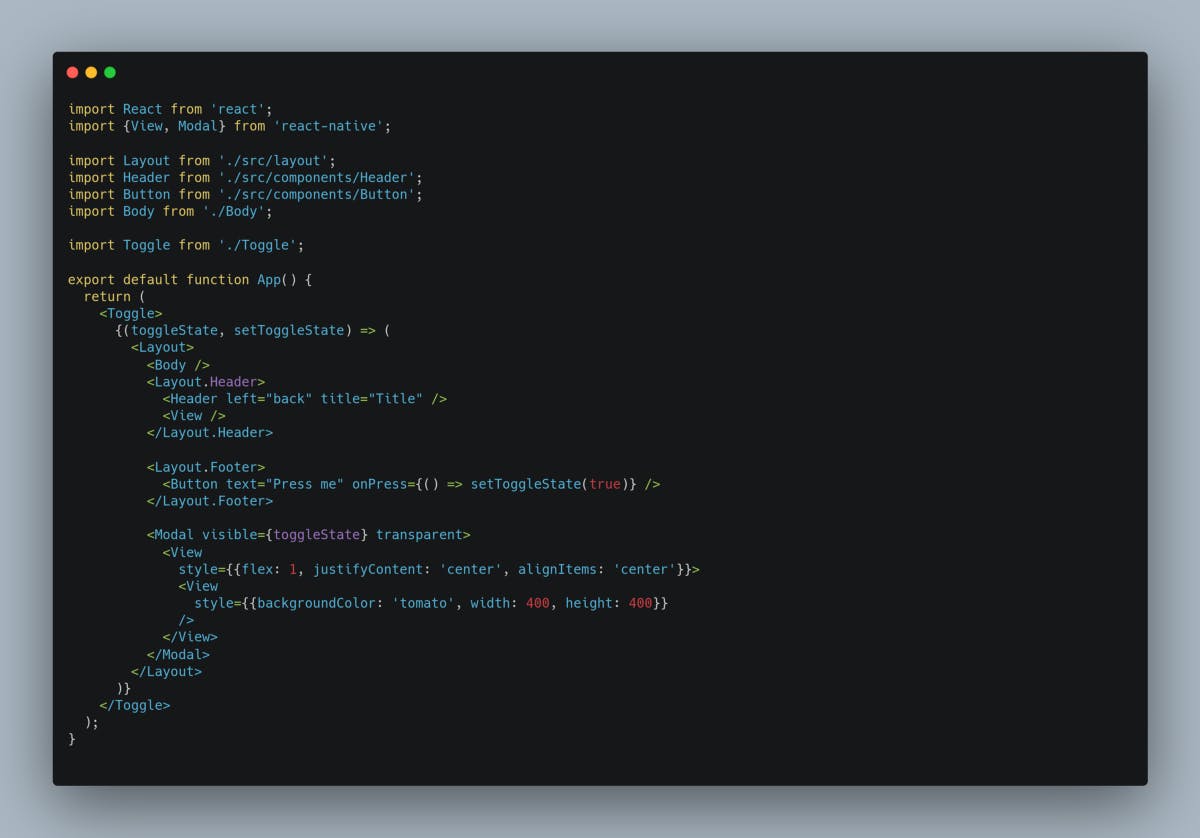

The use of Toggle RPC looks like this:

Hey — we just learned about the compound component pattern above, so why not wrap anything like Modals, Bottom Sheets, or any other things that have to be displayed on top of the actual component separately so that it looks clean? I like to wrap these things with a name called *Overlay*. OK, back to render props…

Here I am passing my whole Layout View to the Toggle RPC as a function using props name render. The props will be invoked passing the toggleState and setToggleState resource back so that when I press the Button it will set the toggle on and Modal is visible.

But instead of passing the Layout View using props name “render” I like to pass it as children of Toggle RPC. Like this:

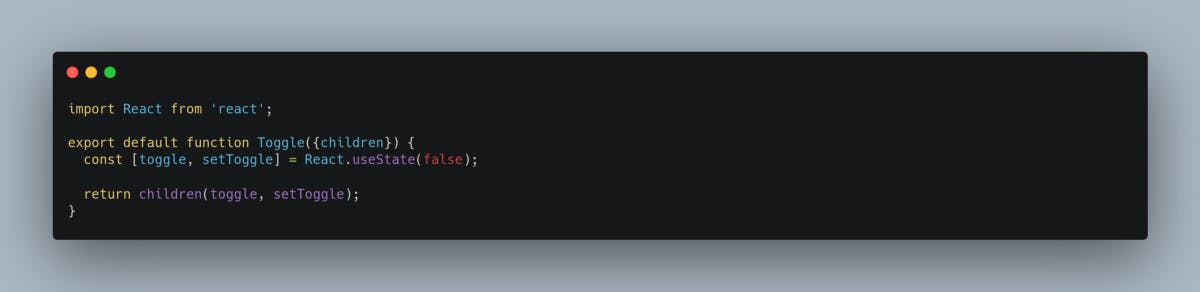

Toggle RPC now looks like this:

You can use as many instances of this RPC as you can in a single component. If you want to toggle a share button here, wrap one toggle inside another as a function and use its state. Remember, every Toggle is an instance so you might think that the state of modal and share may conflict, but it doesn’t.

But the question you may be asking is how is this useful? That’s just one line of React.useState code. I can simply write that state in my main Layout component and use it. Why bother with RPC? Well, let me give you another example and you’ll find out how RPC will change the way you write your code next time.

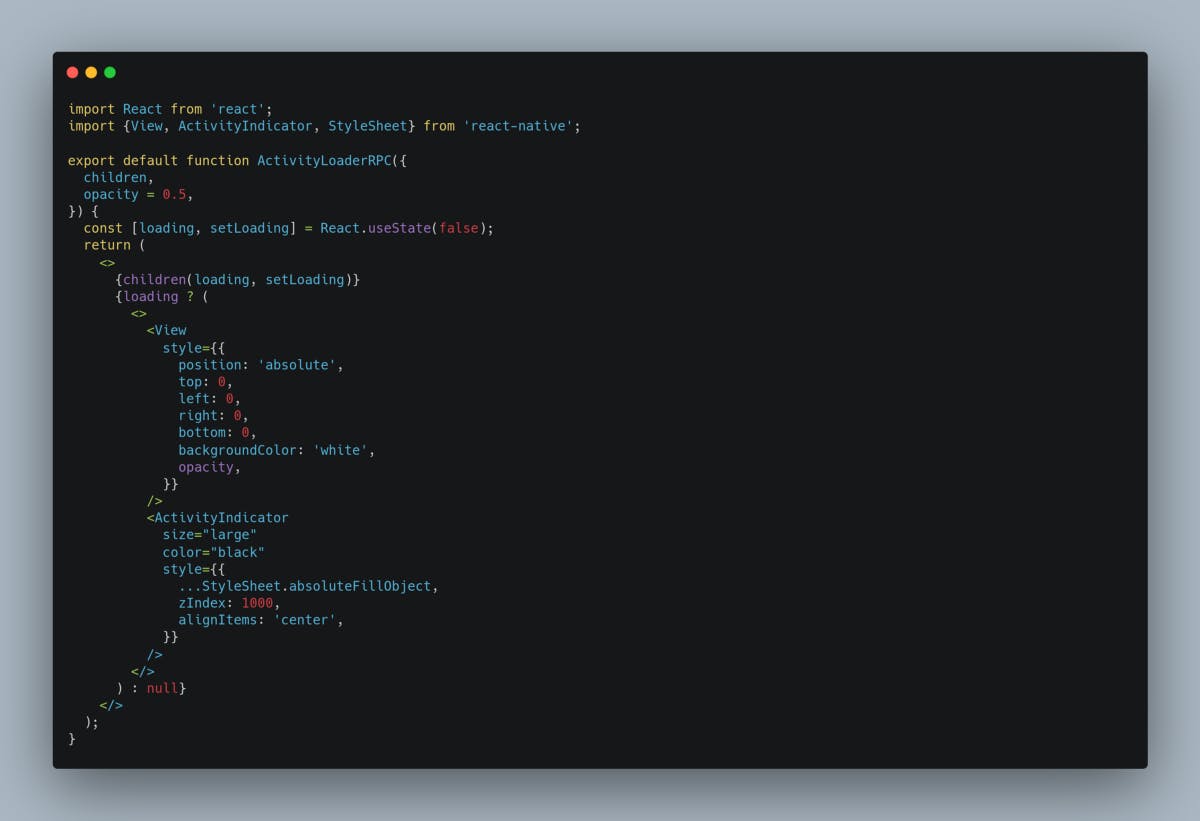

When building a mobile app we often come across a screen that has to display a loader (activity indicator) on top of the whole visible view while making some API calls. The user can’t do anything but wait for that request to finish before they can continue the task. So instead of placing an activity indicator container that is positioned absolute and display it conditionally when loading state is true, we can make a RPC (we will call it ActivityIndicatoRPC) and use that anywhere that applies a similar situation.

This is what the ActivityIndicatorRPC looks like:

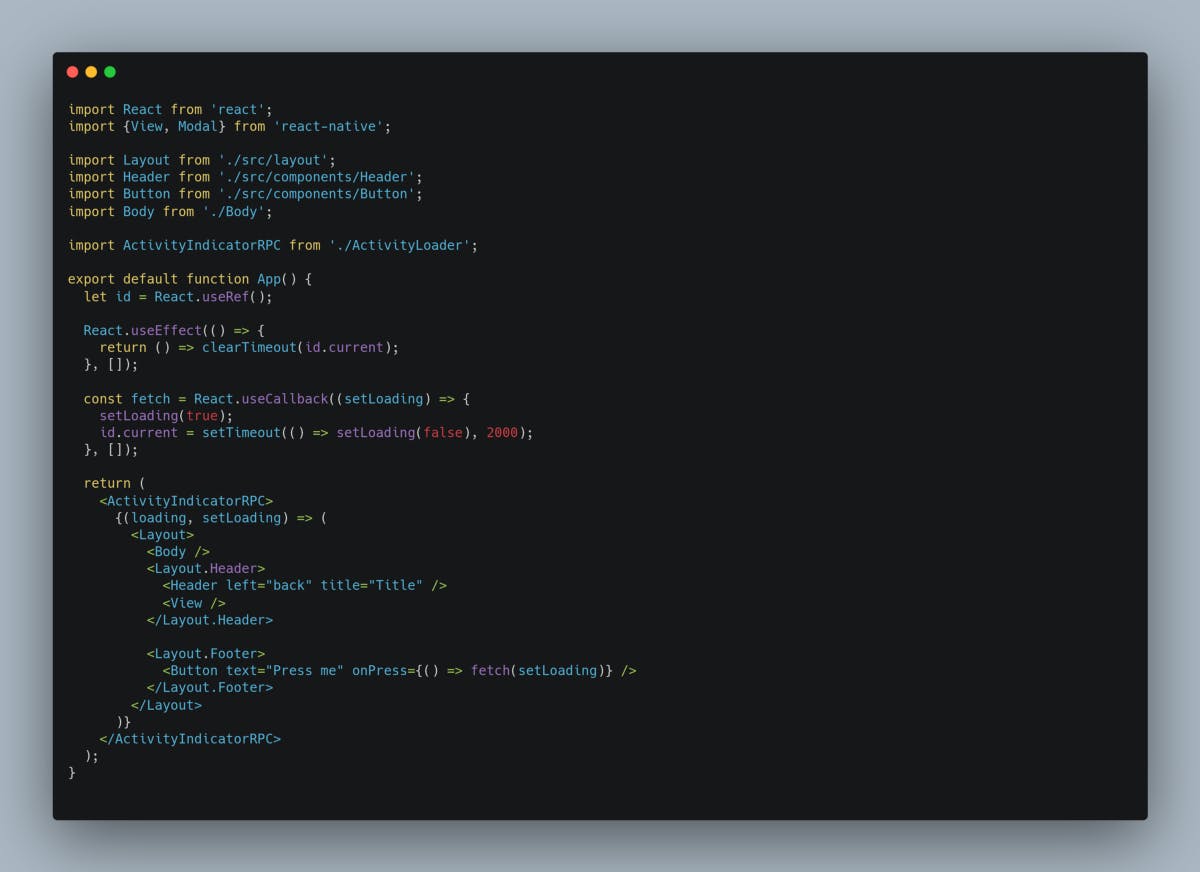

And here is its use case:

See how easy that was? Our main component is very clean because of that RPC. I can now use this RPC anywhere. This is the beauty of the render props component pattern.

3. Higher-Order Component Pattern

The higher-order component pattern and render props component pattern are similar in their functionalities but their implementation is quite different. I use this pattern typically when a screen has to fetch some data from the API for the first time, when a component mounts and that screen is inaccessible to the user until data has been fetched successfully. But if the request fails then there’s nothing to show to the user since it failed so we have to navigate the user back to the previous screen automatically. Here’s how it works.

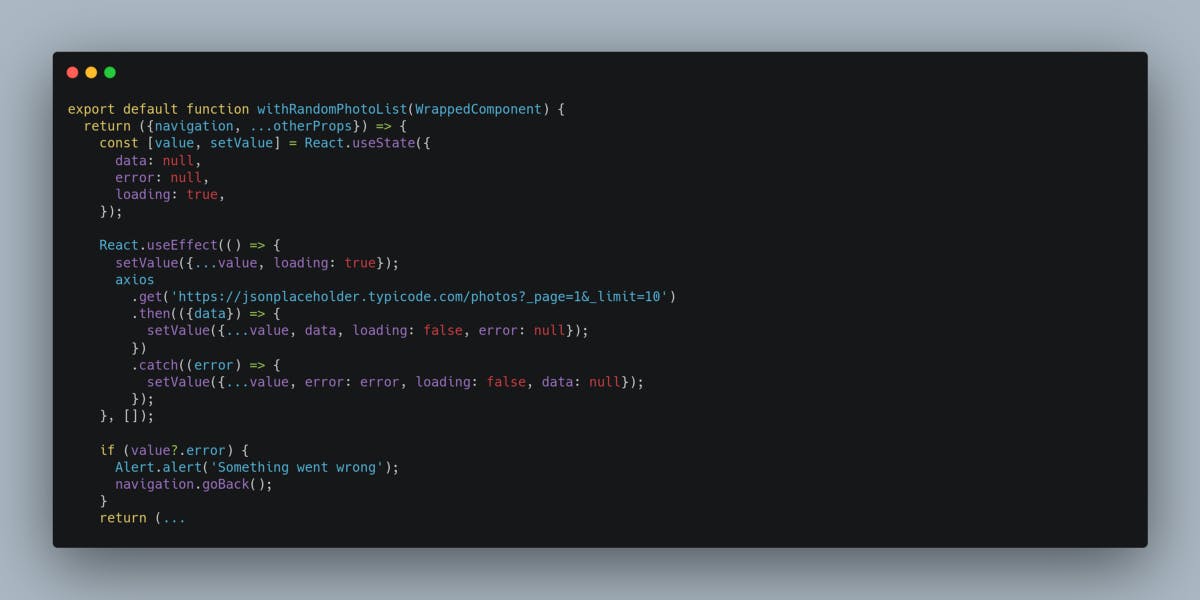

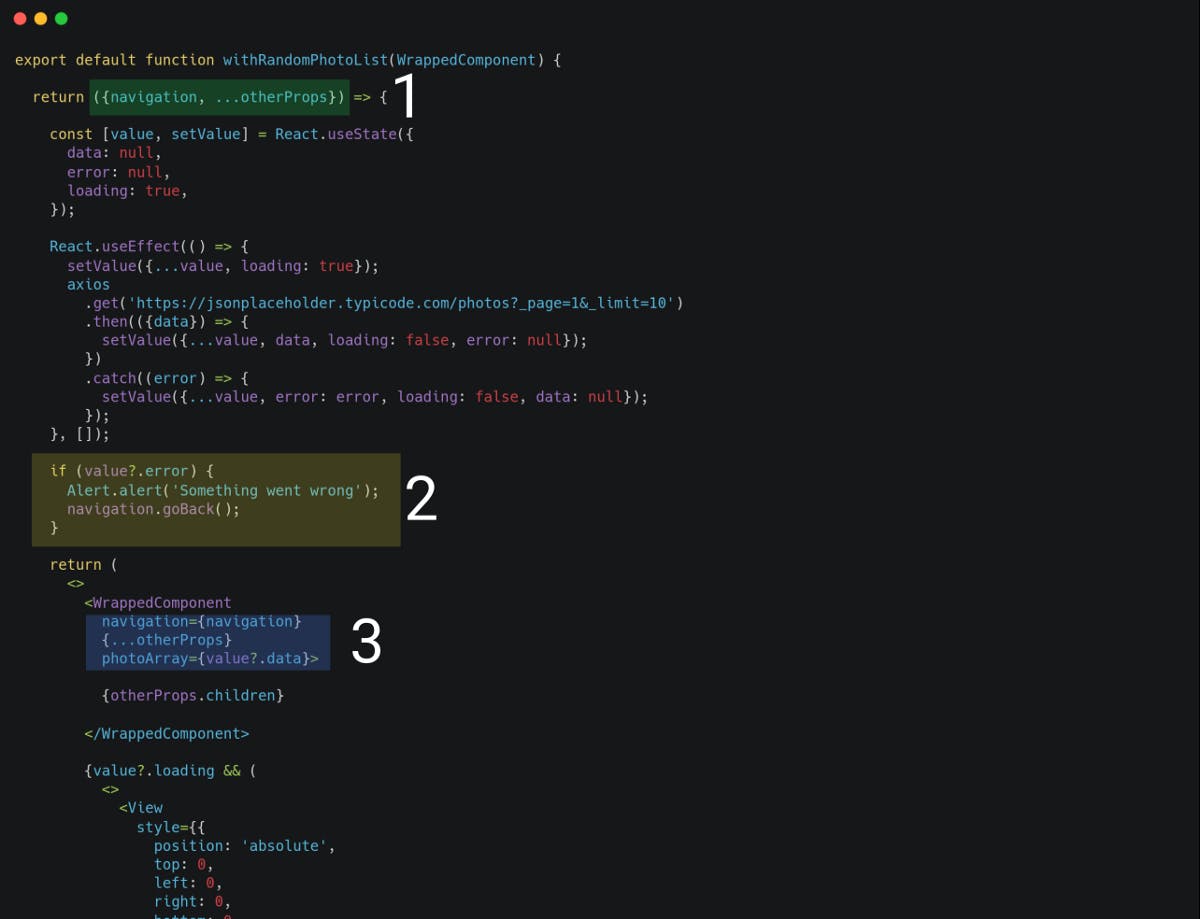

Here’s a simple withRandomPhotoList HOC implementation that queries photo list from [jsonplaceholder](https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/):

withRandomPhotoList HOC

And the use case of this HOC in our App.js looks like this:

Use case of withRandomPhotoList HOC in our Layout component

There’s a lot going on here so let's break it down.

First, we have to wrap the component (or screen in React Native) with this HOC, like this:

export default withRandomPhotoList(App);

Now the HOC accepts this component as an argument. Most people use WrappedComponent as a naming convention.

export default function withRandomPhotoList(WrappedComponent) {

return () => {

...

...

}

So HOC is simply a function that accepts a function as its argument and returns another function after performing some operation on the argument function. So here we are accepting App.js component as an argument and fetching the data from the API and returning another component according to its result.

The props that’s supplied to App.js is received here. The important thing is we must supply all the props back to WrappedComonent, in addition to the other props you want to pass.

- We accept the props of App.js (navigation is a prop that is automatically passed into each screen in React Native if that screen is inside a navigation container. It is similar to Router in Reactjs).

- Navigate back if there is an error during fetch and show alert.

- Pass the data obtained from fetch to App.js along with its own props (important).

So, when loading is true it displays that activity indicator and the user has to wait until it’s finished. When the query is successful, App.js accepts the photoArray data and display the images in FlatList.

Accept the photoArray prop and display it

Display the data

Automatically navigates back and shows alert when there’s fetch error.

HOC can also be used to check permission using withCameraPermission, withStoragePermission, etc and navigate the user to the settings if permission is turned off completely.

That’s it, folks. These are the three React component patterns that I use in every single project. I hope you guys got a good idea about these commonly used patterns and will apply them in your next project. Stay tuned for some more component patterns in the future.